地球環境対策をめぐる最前線

沖村 理史(教授)

*この記事は『Hiroshima Research News』58号に掲載されたものです。

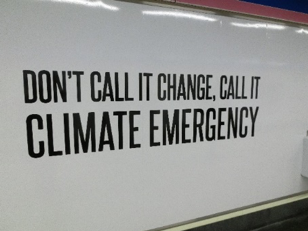

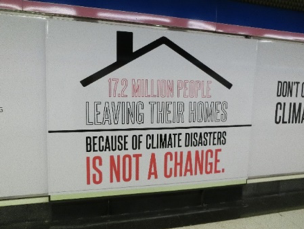

地球環境問題の典型とされる地球温暖化問題は、国際社会では気候変動問題と呼ばれるのが一般的である。実際に、ノーベル平和賞を2007年に受賞した気候変動に関する政府間パネル(IPCC)が1990年から作成している評価報告書のタイトルでは、一貫して気候変動という言葉が用いられている。日本でよく用いられる地球温暖化という言葉からは、地球が徐々に温まるというニュアンスが汲み取れるが、気候変動という言葉からは昨今の異常気象が想起されるのではないだろうか。2019年12月に開催された国連気候変動枠組条約第25回締約国会議(COP25)の会場では、さらに一歩進み、気候変動(climate change)ではなく気候危機(climate crisis)や気候緊急事態(climate emergency)という言葉が数多く用いられた。以下の二枚の写真は、COP25の会場最寄りの地下鉄駅を出た通路にあった広告である。この広告は、気候変動というニュアンスを超える気候緊急事態が現在起こっていると問題提起し、解決に向けた行動が今すぐ求められていると会議参加者を含む多くの市民に訴えかけている。

では気温上昇が進み気候変動が進むと、どのようなことが起こるのであろうか。降雨パターンの変化のように、近年日本で観測されている異常気象の頻発化が、まずは身近に感じられる例であろう。また、気温上昇による熱波や乾燥化、さらに大雨、洪水、少雨などの降雨パターンの変化による居住状況や植生・農業などへの悪影響などもあげられる。この結果、先進国に比べてこれらの悪影響への適応能力に乏しい発展途上国では、気候移民と呼ばれる居住地を離れる状況が起こったり、水資源や恵まれた土地資源をめぐって紛争が起こることが懸念されている。もちろん先進国においても、気候変動の悪影響による社会的なコストが非常に大きいことは、2018年の西日本豪雨を経験した広島では容易に納得できるのではないか。また、2019年の相次ぐ台風襲来に見舞われた東日本や、2019年9月から続く深刻な森林火災に見舞われているオーストラリアからのニュースに触れるにつれ、気候緊急事態だと身近に感じる機会が増えていると言えよう。

2015年に合意されたパリ協定では、今世紀末までの気温上昇を産業革命以前に比べて、2度より十分に下回るものに抑えるとともに、1.5度に抑える努力を継続すること、と定めている。IPCCが2018年にまとめた1.5度特別報告書では、1.5度と2度の上昇では影響に相当程度の違いがあり、1.5度の方が安全であるとされた。しかし、国連環境計画の最新の報告書(Emissions Gap Report 2019)では、産業革命以前の世界の平均気温からすでに、1.1度上昇しており、パリ協定に基づき各国が現在約束している対策が実施されても、21世紀末では3.2度上昇すると見込まれている。残念ながら、気候変動による悪影響は今後も続き、生活環境はこれまでと同様ではなくなり、悪化傾向にあると見通されている。

気象庁が観測している岩手県の綾里の二酸化炭素濃度は、国連気候変動枠組条約が成立した1992年には、358.6ppmであり、京都議定書が成立した1997年には、366.5ppmに上昇した。京都議定書の後継体制を定める目標年として当初想定されていた2009年の濃度は、389.8ppmで、京都議定書の後継体制となるパリ協定が合意された2015年の濃度は、403.4ppmに至った。2018年の濃度(速報値)は、412.0ppmで、この26年間で50ppm以上も上昇している。毎年開催される国連気候変動枠組条約締約国会議が1995年に始まってから四半世紀が経過しているが、その間、二酸化炭素濃度は一貫して上昇を続けているのである。気候変動交渉の場においても、今後の行動指針を決定したパリ協定の合意後、温室効果ガス排出削減の行動を求める声がより一層高まっている。2016年からはマラケシュ世界気候行動パートナーシップが始まり、毎年エネルギーや産業などテーマ別の会議や地域ごとの会議の成果を報告書としてまとめ、政府レベルのみならず、企業や市民レベルの活動を喚起するように努めている。しかし、残念ながらその活動の広がりは気候変動に関心がある人々にとどまっている。そこで、COP25では、会議ロゴの中にTime to Actionという言葉を盛り込み、気候緊急事態への行動がいままさに求められていると視覚的にも強調し、報道等を通じて市民に温室効果ガス排出削減行動の必要性を訴えかけた。

このような中、2019年のノーベル平和賞候補者にあげられた16歳の環境活動家のグレタ・トゥーンベリ(Greta Thunberg)さんは、2018年から学校ストライキを始めた。TED.comでグレタ・トゥーンベリと入力し検索すると日本語字幕付きで聞くことができるスピーチの中で、彼女はストライキを始めた経緯を語っている(”Greta Thunberg: The disarming case to act right now on climate change,” 2020年1月20日最終アクセス)。彼女の運動は若者を中心に大きな支持を生み、Friday for Future という若者が将来の気候や地球環境を問いかけ、気候変動対策の即時実施を求める全世界での運動につながった。2018年12月に開催されたCOP24でのトゥーンベリさんのスピーチは、気候危機を危機として扱わないと危機は解決しないと主張する厳しい内容のものであったが、抑制のきいた話し方をしていた。しかし、その後も行動が広がらない中、2019年9月の国連気候行動サミットでの演説ではより厳しい内容を厳しい口調で訴えかけた。ノーベル平和賞発表を一ヶ月後に控えた時期でもあったため、彼女の演説は報道でも大きく取り上げられ、賛否両論を生み、現在に至っている。

気候変動対策に見られる国際社会の変革と国際平和の実現を求める声は、市民社会に広がったとしても、国際体制が変わるまでには時間がかかるのが国際政治の現実であろう。しかし、地球温暖化ではなく、気候危機、あるいは気候緊急事態を前にして、社会や経済の変革の動きは世界中のそこここで表れており、その動きは拡大しつつある。気候変動による悪影響をできる限り抑制したいというパリ協定がどのように実効性を持つのか、気候変動対策の最前線は、国際社会の取り組みという漠然とした他人事の中ではなく、我々一人一人の市民の行動の中にあるのではないだろうか。

Forefront of Global Environmental Action

OKIMURA, Tadashi (Professor)

*This article is from Hiroshima Research News #58.

The issue often called “chikyu-ondanka” (global warming) in Japanese, viewed as a typical global environmental issue, is generally called “climate change” internationally. In fact, Assessment Reports compiled since 1990 by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the 2007 Nobel Peace Prize laureate, have consistently used the term “climate change” in their titles. While the often-used “chikyu-ondanka” implies that the earth is warming gradually, I suppose that “climate change” may remind many people of the recent cases of extreme weather. At the venue of the 25th Session of the Conference of the Parties (COP 25) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), held in December 2019, further steps were taken to emphasize the terms “climate crisis” and “climate emergency” instead of “climate change.” The two photos below show advertisements posted along a passage from the subway station nearest to the COP 25 venue. These advertisements pointed out that the situation we are now seeing arise should no longer be described by the term “climate change” but instead be called “climate emergency” and urged many citizens, including conference attendees, to take urgent action to solve the issue.

What will result from further rises in temperature and climate change? A familiar example may be the increased frequency of extreme weather, such as changes in rainfall patterns as recently observed in Japan. Other examples include heat waves and increased dryness due to temperature increases, and the adverse impacts on the living environment, vegetation, agriculture, etc. of changes in rainfall patterns, such as heavy downpours, floods, and droughts. There has been growing concern that these can force people in developing countries, which lack the ability to adapt to these adverse impacts compared with developed countries, to leave their homes as climate migrants or cause conflict over water resources and fertile soil resources. I believe that people in Hiroshima, who experienced successive torrential downpours in western Japan in 2018, can easily understand that the adverse impacts of climate change will also incur very high social costs in developed countries. As seen in the successive typhoons that struck eastern Japan in 2019 and news coverage of severe forest fires that have affected Australia since September 2019, it can be said that we are more frequently finding ourselves in situations that can be described as a climate emergency.

The Paris Agreement adopted in 2015 stipulates holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. The Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5°C, published by the IPCC in 2018, asserts that robust differences are expected if global warming reaches 1.5°C versus 2°C above pre-industrial levels, and that limiting global warming to 1.5°C will be safer than 2°C. However, the UN Environmental Programme’s latest report (Emissions Gap Report 2019) finds that global temperatures have already increased by 1.1°C above pre-industrial levels, and that, if all unconditional Nationally Determined Contributions under the Paris Agreement are fully implemented, there is a 66% chance that the warming will be limited to 3.2°C by the end of the century. It is projected, regrettably, that we will continue to suffer the adverse impacts of climate change, and that our living environment will not remain the same as today but will deteriorate.

The atmospheric CO2 concentration measured in Ryori, Iwate Prefecture, by the Japan Meteorological Agency increased from 358.6 ppm in 1992, when the UNFCCC was adopted, to 366.5 ppm in 1997, when the Kyoto Protocol was adopted. In 2009, which was initially planned to be the target year for the decision on the next regime following the Kyoto Protocol, the concentration was 389.8 ppm. In 2015, when the Paris Agreement was adopted as the regime following the Kyoto Protocol, the concentration amounted to 403.4 ppm. The concentration in 2018 (preliminary figure) was 412.0 ppm, which is more than a 50 ppm increase in 26 years. While a quarter century has already passed since the first session of the UNFCCC COP was held in 1995, the atmospheric CO2 concentration has continuously increased during this period. Since the Paris Agreement was adopted as subsequent action guidelines, effective action to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions has been more strongly pursued in climate change negotiations. In the Marrakech Partnership for Global Climate Action, launched in 2016, the results of conferences by theme, such as energy and industry, or by region are compiled into annual reports to inspire not only governmental but also corporate and civil action. Nevertheless, such action has spread only among people interested in climate change. To address this situation, COP 25 used a logo including the motto “Time for Action” to visually highlight the urgent necessity of action to address the climate emergency, and the conference also delivered a strong message through the media to citizens about the necessity for action to reduce GHG emissions.

Against such a backdrop, the 16-year-old environmental activist Greta Thunberg, who was widely seen as a candidate for the 2019 Nobel Peace Prize, launched a school strike in 2018. In her speech posted on TED.com (Japanese subtitles available), she describes what made her start the strike (“Greta Thunberg: The disarming case to act right now on climate change.” Retrieved January 20, 2020). Her movement has attracted a large number of supporters, especially among the young, leading to a worldwide movement named Friday for Future for young people advocating immediate action to address climate change. Her speech at COP 24 in December 2018 was given in a restrained manner despite its strident message that “We cannot solve a crisis without treating it as a crisis.” Nevertheless, significant action did not follow in a satisfactory manner after that. In response to this situation, Greta delivered a speech with a harsher tone and content at the 2019 UN Climate Action Summit. Since it was one month before the announcement of that year’s Nobel Peace Prize, her speech received massive media coverage and triggered heated controversy, which has continued until today.

It might be a reality of international politics that, even if the appeal for revolutionary change in the international community, such as climate change action, or international peace is widely accepted by civil society, it will take a long time for the international regime to change. However, in response to the climate crisis or climate emergency, rather than climate change, movements toward social or economic reforms have emerged and been expanding around the world. I believe that the answer to the question of how effective the Paris Agreement will ultimately be in mitigating the adverse impacts of climate change may be in the action that every one of us takes, instead of being in vaguely imagined international initiatives that remain someone else’s responsibility.